We have written extensively about the OECD’s so-called “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)” project to tackle tax cheating by multinational companies.

The BEPS project has 15 “Actions” for reform, and Action 11 is called “Measuring and Monitoring BEPS.” The intention here was to draw together existing data to create a baseline for the scale of the problem, to better understand its nature and to be able to track progress over time.

Yet no such baseline has been delivered: despite some committed work by the staff involved, major OECD members resisted even the minimal transparency of allowing companies’ country-by-country reporting to be centrally collated and analysed.

The need for new research

New research in this area is sorely needed. UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2015 found that one form of profit-shifting alone cost developing countries around $100 billion a year in lost revenues. Researchers at the International Monetary Fund put the overall revenue loss for developing countries at about twice that, and the global total nearer $600 billion a year.

None of these studies provide a breakdown identifying the winners and losers. An earlier study be Cobham & Loretz in 2014, revealed mainly that data coverage, especially for developing countries, was simply too poor. But for the sample that was available, it was clear that the poorest countries suffered the most extreme profit-shifting.

Now, using a relatively under-exploited dataset covering all multinationals headquartered in the United States, we at TJN have been able to broaden the analysis.

Main findings

Three main findings stand out.

First, BEPS is a problem of first-order importance in terms of the world economy.

An estimated $660bn of corporate profits were shifted in 2012 — or more than a quarter of US multinationals’ gross profits . That sum is equivalent to 0.9% of world GDP.

Second, countries at all incomes levels are losing out to profit-shifting – while most of this ‘missing’ profit ends up in just a few jurisdictions with near-zero effective tax rates – notably Netherlands, Ireland, Bermuda, Luxembourg (the most important by far) as well as Singapore and Switzerland.

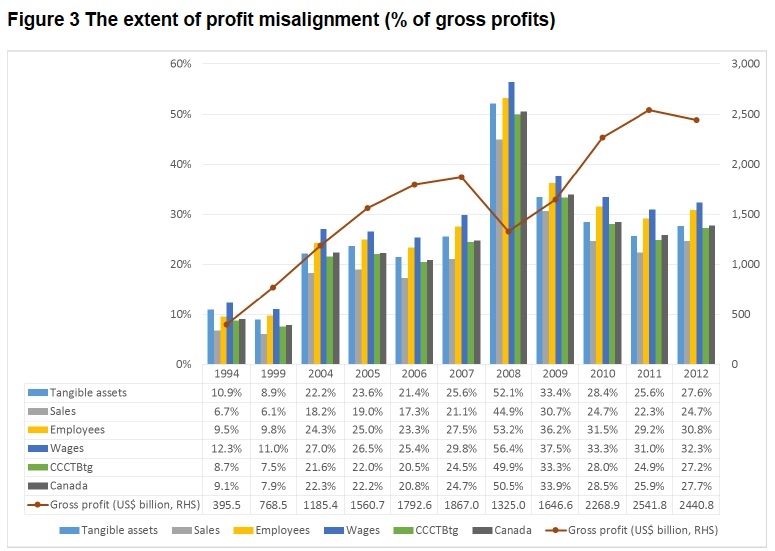

Third, profit-shifting by US multinationals has grown sharply over the last two decades. Figure 3 shows, for various measures of economic activity, profit-shifting as a share of total gross profits.

In the immediate post-crisis period, profit-shifting stands at 25-30% of total profits, higher than in the pre-crisis early 2000s, which was in turn sharply higher than the mere 5-10% of the 1990s.

It’s a newish phenomenon, and getting worse

So this widespread profit-shifting is a relatively new phenomenon, and this is despite falling tax rates – (or, to be more precise, a narrowing difference in effective tax rates between the corporate tax havens like Bermuda, and the rest.)

This is counter-intuitive: one might have expected that as a country tries to become more like a tax haven and this differential narrows, this would reduce the incentive for multinationals to shift profits out of that country. Yet the opposite is happening: amid all this tax-cutting, the profit-shifting is getting worse.

This is a tremendously important finding – for it suggests that the race to the bottom among major economies like the UK has simply given away corporate tax revenues. (See our Fools’ Gold site for more on tax ‘competitiveness’.)

Finally, this confirmation of the scale of misalignment between where genuine economic activity happens and where the profits are reported (and the extent to which most countries are losing out to a handful of jurisdictions) should focus our minds on the importance of better data to track BEPS and to ensure progress is made. Individual countries, jurisdictions and economic blocs must urgently make country-by-country reporting public.

Full paper and data annex

The full paper behind the report is published in the peer-reviewed working paper series of the International Centre for Tax and Development – the leading international and interdisciplinary academic centre in its field, funded by the UK and Norwegian governments:

Full ICTD working paper and the data annex: Cobham Jansky 2015 – Data annexes.

Further reading

- Mar 2016 – Ending the Era of Tax Havens (Oxfam / Alex Cobham). Containing two separate scale estimates, one in each of Sections 2 and 3.

- 2010 – Microsoft moving profits, not jobs, out of the U.S. – Marty Sullivan, Tax Analysts. Containing graphs confirming the recent nature of the phenomenon.