Tax ‘competition’ and tax wars

Tax Competition is the process by which countries, states or even cities use tax cuts, tax breaks, tax loopholes or tax subsidies to attract investment, hot money and even wealthy individuals.

In response to ‘competitive’ pressures they cut taxes on wealthy individuals or on corporations – which are generally more mobile than poorer people or smaller and local businesses – and this has knock-on effects: not least that countries then make up the difference either by hiking taxes on poorer sections of society, or cutting spending, or increasing budget deficits.

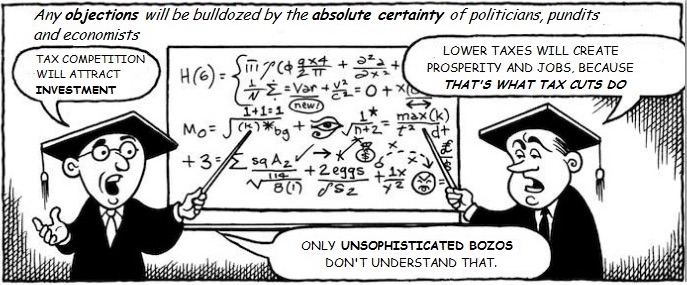

Assertions that tax ‘competition’ somehow stimulates economic growth or otherwise benefits the economy have been thoroughly discredited. Yet it remains quite a popular view.

We prefer the term ‘tax wars‘ instead of ‘tax competition,’ for two main reasons.

First, competition between countries is nothing like competition between companies in a market (to get a sense of this, ponder the difference between a failed company and a failed state.) So it is confusing to call this ‘competition:’ this beggar-my-neighbour game is rather more like currency wars or trade wars between countries. Second, tax ‘competition’ is always harmful: we think ‘tax wars’ does a better job of conveying the harm. (Some also use the term ‘tax dumping‘, for similar reasons.)

See our short article exploding a myth that a ‘competitive’ tax system is a good thing.

See our full report entitled Ten Reasons to Defend the Corporation Tax.

See Competitiveness – Was Charles Tiebout Joking?

See John Christensen discussing tax wars (2m:53).

“The notion of the competitiveness of countries, on the model of the competitiveness of companies, is nonsense.”

– Martin Wolf, chief economics writer, Financial Times

At a global level, tax competition creates a race to the bottom – and we believe it has no redeeming features. It is always harmful, particularly for larger economies. As well as boosting inequality it erodes democracy, distorts markets, subsidises unproductive rent-seeking, kills jobs by subsidising capital at the expense of labour, reduces productivity and economic growth, and boosts monopolies and market power by rewarding the biggest and most internationally mobile players at the expense of smaller, more local players.

Tax wars bite all countries – but it hurts developing countries particularly hard.

Why tax competition and supposedly ‘competitive’ tax systems are harmful

At a national level, all the evidence shows that it is a mistake to try and create a ‘competitive’ tax system, strange though that may sound.

This is for several reasons.

As mentioned above tax ‘competition’ bears no economic relation to competition between firms in a market. They are different economic beasts, which share a word in the English language: ‘competition’. Because of this word, many people who haven’t thought too hard about the issues see this as a beneficial process. It’s not.

In addition, tax is not a cost to an economy, but a transfer within it. Tax cuts for corporations provide subsidies to them, at the expense of another essential wealth-generating mechanism: public spending on roads or courts or education, and so on. So it is not obvious how corporate tax cuts make any country any more ‘competitive’ – whatever ‘competitive’ may mean.

It may be that cutting taxes attracts investment – but the general evidence out there on this point is extremely shaky. Even in the cases where it does attract investment, it tends to attract exactly the wrong kind: the flighty stuff with few productive linkages with the rest of the economy. If it’s good, embedded investment, then it won’t be chased away by a whiff of tax.

Even Ireland, the poster-child for supposedly ‘beneficial’ tax competition, is not at all what it seems, and not an example other countries can or should follow.

The fantasy of beneficial tax competition

things because of inducements.”

-Paul O’Neill, ex chair of Alcoa

The theory that tax wars are a good thing rests heavily on a paper written in 1956 by the U.S. economist Charles Tiebout. The idea he put forwards was that people would move to jusrisdictions which offered them the best mix of taxes and services, and this resulted in the sorting of jurisdictions into ‘optimal’ communities. The paper, however, relies on unspeakable assumptions – for example, that tax havens don’t exist – or that hordes of perfectly informed citizens rip their kids out of schools flit in huge shoals from one country to another, every time the tax rate changes. These and other similarly unworldly assumptions render the paper unworkable.

Although the arguments can get quite complicated, not least because of the large number of academic studies out there straining the morass of evidence to show that tax wars provide benefits, our short article provides a useful introduction to the issue, explaining the problems.

If you use the term tax competition, perhaps put ‘competition’ in quote marks, even if only to signal that you understand the issues.

Copyright 2014 by Michael Goodwin. Illustrations from Dan E. Burr; text adapted by authors. Permission with thanks to Michael Goodwin

Solutions

There are two general approaches that are needed to tackle tax wars.

- Co-ordination and co-operation. Tax wars are a classic ‘collective action‘ problem. At a global level, the process involves in a race to the bottom. The end result is a race to (for example) zero corporate tax rates – which would create immense damage to the world economy. The answer to collective active problems is co-ordination and co-operation between states, to reach agreement not to engage in such a race. However, as with collective action problems in general, there is a strong urge to cheat. This means another approach needs to complement the first.

- Change the ideology. Not only is the race to the bottom harmful, but it has been demonstrated — particularly for larger economies — that even from the perspective of pure national self-interest, it generally makes no sense to engage in the race to the bottom on tax. Many tax cuts are driven by ideology rather than evidence.