Tax avoidance is probably the most misunderstood and misused word in the field of tax. We rarely use the word: we prefer terms like ‘tax cheating’ or ‘tax dodging’ or ‘escaping tax’ instead.

Here’s why.

Is tax avoidance legitimate?

In a word, no: for two reasons. First, what often gets called avoidance isn’t ‘legal’, as this page explains. Second, what is legal isn’t necessarily legitimate. (Apartheid was legal, in its day.)

Tax avoidance or tax evasion?

The big confusion about ‘tax avoidance’ arises because it hinges on the question of whether the tax arrangement is legal or not. The traditional definitions say that tax avoidance is legal, in contrast to ‘tax evasion’ which is illegal (usually by fraudulently under-declaring or not declaring a tax liability).

This comes with a twist: as one definition of tax avoidance presented in the British House of Lords: “Tax avoidance …. is a course of action designed to conflict with or defeat the evident intention of Parliament.” In other words, tax avoidance complies with law, but it goes against the spirit of what our legislators intended.

That’s the traditional story.

The main problem with this story is that a lot of what gets called ‘tax avoidance’ is actually something else, which often lies in a grey or uncertain area between avoidance and evasion. In fact, much of what gets called ‘avoidance’ turns out to be rather more like evasion: it involves pocketing tax money that legally should be paid. It’s just that they don’t get noticed or successfully challenged or caught out.

This happens all the time. Multinational companies, egged on by tax advisory firms which can reap huge profits from selling dodgy tax schemes, routinely push the boundaries of our tax laws, with varying degrees of aggression. In 2013 the UK’s Public Accounts Committee, a government watchdog, heard testimony from a senior official at a Big Four accountancy firm that they would sell tax schemes to clients even if they thought there was only a 25 percent chance they would survive a court challenge.

“I am aware of instances where a single planning idea has generated fees of £100m”

– Jolyon Maugham, tax barrister

Yet media organisations and many others still use the term ‘tax avoidance’ to describe dodgy schemes: and that’s often because their libel lawyers tell them this term is less likely to get them sued. Journalists mistakenly write ‘avoidance’ if they cannot show that the company has broken the tax laws. But this is wrong: they should only write ‘avoidance’ when they can show that the company hasn’t broken the tax laws, but has still got around the rules. While their caution is quite understandable, this makes their reports no less inaccurate.

Sidestep thorny questions of legality: focus on the economic and the political

In light of all this uncertainty, we prefer terms like ‘tax cheating,’ ‘tax dodging‘, ‘tax abuse‘, or ‘escaping tax‘. These terms skip neatly over the question of whether a given structure is legal or not, and focus instead on the essential issues, notably the economic and political aspects of what’s going on. (Apple’s CEO Tim Cook highlighted this in August 2016 when he said a demand from the European Commission to pay a €13bn back tax bill was “total political crap”.) Some of these terms are morally loaded: and in light of the politics and economics of what is going on, that is often appropriate.

Foreign language confusions

Adding to the confusion, foreign-language terms in this area don’t generally mean what you might think. For example, the French term évasion fiscale is best translated as tax avoidance. (The closest French translation for tax evasion is fraude fiscale.) Beware.

Schemes that get given the ‘tax avoidance’ label typically involve economic transfers away from one interest group, typically ordinary taxpayers who can’t hire expensive accountants to set up such schemes, to another interest group, typically wealthy individuals or large multinational corporations. This tends to increase inequality and damage democracy.

Risk mining

Let’s take an example. BigCorp uses transfer pricing tricks to shift as much of its profit as possible away from Tanzania, say, into a zero-tax haven. BigCorp hasn’t operated in good faith within the law.

Usually, BigCorp will get away with it (this is particularly true with poorer countries, whose tax authorities don’t have the expertise to find the scheme or to challenge the multinational’s highly paid legal teams.) BigCorp escapes paying a Tanzanian tax bill that was legally due.

See this for what it is: a hidden (and illegal) transfer of wealth from Tanzania to BigCorp.

Often, Big Corp won’t be sure at the outset whether or not their scheme will be challenged in court, or if it would withstand such a challenge. They are taking a chance with the scheme. This is what David Quentin calls “risk mining” – a useful lens through which to understand the phenomenon better. (Click the flow chart here to enlarge it, to get a clearer sense).

Often, Big Corp won’t be sure at the outset whether or not their scheme will be challenged in court, or if it would withstand such a challenge. They are taking a chance with the scheme. This is what David Quentin calls “risk mining” – a useful lens through which to understand the phenomenon better. (Click the flow chart here to enlarge it, to get a clearer sense).

Now imagine that a Tanzanian news organisation exposes BigCorp’s shenanigans. Even though the tax is due according to the law, it may still go unpaid. This may be because BigCorp’s tax directors took the Tanzanian taxman out for an expensive dinner, or the head taxman turns out to be terrified of annoying corporations, or hopes to get a better-paying job with BigCorp, or is an anti-tax zealot — or simply doesn’t have enough information or expertise to know they are being taken for a ride and to take action to stop it. For whatever reason, the authorities still won’t challenge the arrangement.

BigCorp will say: “We haven’t broken any laws.” Journalists may write “this was tax avoidance, and perfectly legal and legitimate.” Their readers sigh, and move on with their lives. And Tanzanian schools, roads and hospitals don’t get built.

Was this ‘tax avoidance?’ It isn’t clear. Best to avoid theterm.

In summary, it’s generally better to stay away from ‘avoidance’ unless you are absolutely sure that no tax laws have been broken. And when writing about the issues, always consider the economic and political aspects.

Where to draw the line?

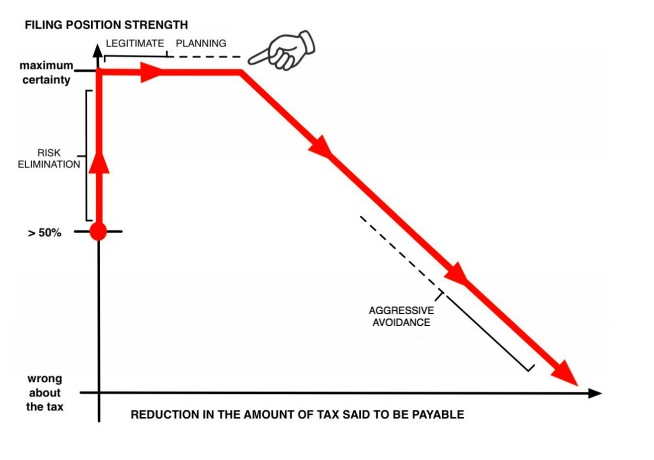

If you want to get technical and you’re keen to draw a line somewhere, it’s more useful to sidestep the maddening grey area between avoidance and evasion and focus instead on the difference between abusive tax arrangements and ‘legitimate tax planning’ (i.e. eliminating tax cock-ups where you pay more than you really should).

This can be combined with the Risk Mining framework into a picture:

Do corporate directors have a duty to their shareholders to avoid tax?

The answer is a straightforward no. Absolutely not.

In fact, the Tax Justice Network obtained a formal legal opinion to this effect in the United Kingdom, from the Queen’s own solicitors, Farrer & Co. (see also here). In the United States, the all-important Delaware courts have also ruled that “there is no general fiduciary duty to minimise taxes.” (In most other countries, this will also be true, though we haven’t conducted an exhaustive survey.)

Company directors generally have duties to promote the success of their companies. But in doing so, they are required to consider a wider set of stakeholders than merely shareholders: they need to balance the interests of their shareholders against the interests of wider society. That gives them wide leeway to decide how far to push the envelope as regards tax avoidance.

In general, payment of tax needs to be part of companies’ corporate responsibility offerings. See much more on this on our permanent Corporate Responsibility webpage.

Is an ISA tax avoidance?

No, it isn’t. An ISA is an Individual Savings Account, where the British tax system allows people to save up to a certain amount of money each year (in 2016 it was around £15,000), and be exempt from tax on the savings income. This zero percent tax rate is analogous to the zero percent tax rate that any progressive tax system levies on the first portion of a citizen’s income: it is just the tax rate.

The ISA is a specific mechanism created by parliament to align the tax regime on savings income with the principles of a progressive tax system. It is not tax avoidance.

Further reading:

Risk mining: what tax avoidance is, and exactly why it’s anti-social – TJN/David Quentin (full paper here.)

Weak transmissions mechanisms – and the boys who won’t say no – Jolyon Maugham, 2014