Tax havens

What is a tax haven? What is a secrecy jurisdiction?

To see what a tax haven really looks like, watch this 60-second video.

There is no generally agreed definition of what a tax haven is. The term is a bit of a misnomer, because these places offer facilities that go far beyond tax. Loosely speaking, a tax haven provides facilities that enable people or entities escape (and frequently undermine) the laws, rules and regulations of other jurisdictions elsewhere, using secrecy as a prime tool. Those rules include tax – but also criminal laws, disclosure rules (transparency,) financial regulation, inheritance rules, and more.

We don’t offer a formal definition of tax haven, but we think that those two words in bold text are key to understanding the phenomenon. Language is important: the word ‘escape’ points to the word ‘haven’ in ‘tax haven,’ and the word ‘elsewhere’ points to the word ‘offshore’, which is another term that we sometimes use when we want to emphasise the ‘elsewhere’ nature of the phenomenon.

We also sometimes use the term ‘secrecy jurisdiction’ instead of tax haven. We take this term to mean a similar thing as ‘tax haven’; we use it when we want to emphasise the secrecy aspect. (We do not offer our own strict definition of a secrecy jurisdiction either, though there are useful definitions out there, such as this one.) See a more detailed discussion of this question here.

Different jurisdictions have different offshore offerings. The British Virgin Islands, for example, specialises in incorporating offshore companies. Ireland is a corporate tax haven and a haven for laxity in financial regulation but not really a secrecy jurisdiction; Switzerland and Luxembourg offer secret banking, corporate tax avoidance and a wide range of other offshore services. The United Kingdom does not itself offer secret banking but it sells an even wider range of offshore services, including lax financial regulation. And so on.

Several international bodies have their own lists of tax havens, which are frequently skewed by political expediency. These lists tend to exclude or downplay large, powerful nations and highlight small, weaker ones. Our own list, the product of years of exhaustive research into financial secrecy, makes no such concessions: it is the Financial Secrecy Index. Click on an individual country to see how it became a secrecy jurisdiction.

Where are the tax havens?

Since there is no generally agreed definition of what a tax haven is, there is no definitive list of them. What is more, nobody likes being called a tax haven: they all deny being one.

Contrary to many people’s perceptions, the offshore world of tax havens (or secrecy jurisdictions) includes some of the world’s biggest economies. Beyond the usual suspects of Switzerland, the Cayman Islands or Panama are jurisdictions that are less often identified as tax havens – such as the United States, United Kingdom and even, on some measures, Germany. See our own widely referenced list of tax havens – the Financial Secrecy Index – which focuses on the secrecy aspect of the offshore issue. Although Switzerland tops our index, we stress that Britain is the single most important player in the offshore system of tax havens, because of its control and support of a wide network of part-British territories (such as the Cayman Islands or Jersey) which are major players in the system. Read more about Britain’s role here.

Given that some of the world’s most powerful and influential nations are important players in the offshore system, it is hardly surprising that several lists of tax havens prepared by the IMF, the OECD and other international bodies are modified for political reasons.

The offshore world is a complex, constantly shifting (and growing) ecosystem, with different players providing different offerings. Some focus largely on secrecy alone: these tend to be smaller and more obscure jurisdictions: see a ranking of them here. They include certain U.S. states such as Delaware, Nevada or Wyoming. Some are not particularly secretive but specialise in offering corporate tax avoidance facilities: examples include Ireland, or the Netherlands or Bermuda or Luxembourg. Some specialise in offering lax financial regulation: for example Luxembourg, or the United Kingdom (see more here.) Some are all-singing, all-dancing tax havens, such as the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Singapore. Some specialise in certain sectors: Bermuda for insurance, for instance, or the Cayman Islands for hedge funds or private equity. Some are more co-operative than others.

How big is the problem?

Since there is no generally agreed definition of what a tax haven is, and because of the secrecy that pervades the system, precise numbers are hard to come by. Contrary to quite widespread popular perception, the offshore phenomenon of tax havens is not an exotic sideshow to global finance: it is now at the heart of the global economy. On some measures, half of all world trade passes – at least on paper – via tax havens.

A range of estimates of aspects of tax haven activity are provided on Our “Magnitudes” page.

The most comprehensive and authoritative single study of the size of the offshore system is our 2012 publication The Price of Offshore Revisited, which estimated conservatively that there is some $21-32 trillion in financial assets sitting offshore, largely untaxed, in conditions of secrecy. That many dollar bills, laid end to end, would stretch more than three times along the earth’s orbit around the sun. This puts the quaint notion of briefcases being smuggled across borders into perspectives. This is about banking transactions and a global infrastructure of private enablers and intermediaries.

Developing countries may seem as if they are collectively big debtors – but their debts are dwarfed by the offshore assets held by their wealthiest citizens. These countries don’t have a debt problem: they have a hidden asset problem.

See our “Magnitudes” page for more.

History: how did tax havens emerge?

This is a complex question, and research is in its infancy. In very general terms, the offshore phenomenon has always existed, in that it has always been possible for wealthy people to take their wealth (or themselves) elsewhere to other jurisdictions, to escape the responsibilities of society at home.

The founding of the Swiss Confederation in 1848 marked the birth of perhaps the first organised and identifiable tax haven – though bankers in Geneva and Zurich had harboured Europeans élite’s’ wealth in conditions of secrecy for years beforehand. Various pirate coves in the Caribbean, the English Channel and elsewhere also hosted what might be described as early offshore activity. The era of financial globalisation from the 1960s onwards marked a new, more virulent phase of offshore activity, as staid and secretive Swiss-styled banking secrecy was complemented by more aggressive, hyperactive Anglo-Saxon strains that took off in the Caribbean and Britain’s nearby Crown Dependencies, alongside Luxembourg and other European havens.

The United States began deliberately putting into place secrecy facilities from the 1970s in particular. European jurisdictions such as Ireland and the Netherlands began to get in the game. Asian havens, notably Hong Kong and Singapore, also have long histories as centres for often illicit offshore finance, and are the fastest-growing segment of the offshore game today.

To read more about the history of tax havens, we would highlight a few resources.

Nicholas Shaxson’s 2011 book Treasure Islands is the most widely referenced book on the subject. (For a shorter summary of some of the historical points, see his article in Vanity Fair, A Tale of Two Londons.) See also Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works, by Ronan Palan, Richard Murphy, Christian Chavagneux.

To explore the offshore histories of individual tax havens, there is a collection of the most important jurisdictions available here. Click on the jurisdiction that interests you.

For a series of links looking at particular aspects of the offshore phenomenon, click here.

How do we tackle tax haven abuses?

There is no magic bullet to solve these problems. Or if there is a magic bullet, it is this: citizens and public opinion must push politicians in countries around the world to address the problems. The system of offshore tax havens is organised and tolerated by Britain, the United States and various other rich countries. Citizen pressure here is essential. But every country in the world is impacted by tax abuses and tax havens. This is a battle that affects literally everyone in the world.

Before change is possible, people must understand two things.

First, the offshore system of tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions isn’t where most people think it is: small islands and secretive Alpine principalities. It is, increasingly, in the large and supposedly ‘onshore’ economies. See a list of the most important players here, viewed from a secrecy perspective. Second, the problem is much, much bigger than is commonly supposed. We estimate that there is at the very least $21 trillion sitting off shore, largely untaxed and out of reach of the rules of democratic societies.

As regards more concrete measures to tackle tax havens, there are far too many to mention here in full: the rest of our website offers a wide range of pointers. Transparency is one obvious big theme, with many moving parts. Transforming the international corporate tax system is another: see here for a real way forwards. Recognising the harm caused by tax (and regulatory) competition between nations is another: see here for more. Facing down the private enablers of the system – the banks, big accountancy and legal firms, and so on – is another essential and often-overlooked ingredient in any strategy: see here for more. Injecting all these elements into the economics profession in particular, and shaking up discredited old models, is also crucial.

We are making amazing headway on all of these – but with a very, very long way still to go. Please support us by learning about the issues, spreading the word, and taking action.

Will we ever get rid of tax havens?

In a word, no. We’ll never get rid of crime, either. It will always be possible to take your assets elsewhere to escape the rules of the society where you live.

But there is a multitude of actions that will tackle the abuses that are facilitated and encouraged by tax havens. There are too many to mention here: the rest of this site explores many of these avenues.

Some people argue that it isn’t possible to crack down on offshore abuses: it will merely displace the problem somewhere else, they say, like squeezing a balloon at one end. But this is to misunderstand the problem. When you squeeze a balloon, the shape changes but the volume remains the same. Tackling tax havens is different. When you crack down in one area, you will catch some of it, and some will escape. The overall size of the problem will diminish. It is more like squeezing a sponge.

And by the way, when we say ‘tax havens’ – it is important to distinguish between the place that hosts the offshore activities – and the activity itself. It is the latter that we’re interested in. We have nothing against, say, the Cayman Islands. It is their offshore financial services activity that interests us.

Whose job is it to tackle tax havens?

Each country can put in place steps to protect itself from the damage caused by tax havens, whether that damage comes in the area of tax, organised crime, lax financial regulation, and so on. These measures, far too many to detail here, are essential. But these problems cross national boundaries, and so it’s necessary for regional and international bodies to play a role. A large number of tax havens, as our Financial Secrecy Index shows, are the responsibility of one ‘mother’ country – particularly Britain, with its Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. Britain controls these places and could do a lot to close down the abuses. The European Union also has a lot of power to tackle these places, but, like Britain, policy-making is infested with tax haven vested interests, and some member states like Luxembourg, which have veto powers in many areas, are able to influence debates and block legislation.

On a global level, the OECD, a club of rich countries, play a powerful role. The United Nations, which is a more representative body and includes many of the worst victims of tax havens abuses in developing countries, has been effectively sidelined in the rule-making process, even though it is the more legitimate forum. There are a number of other initiatives. See, for example, Who Makes the Rules on Illicit Financial Flows, Financial Transparency Coalition,

https://financialtransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/WhoMakesTheRules_2.22.17.pdf

Tax justice

What is tax justice?

Tax justice has evolved to mean more than what it says on the tin. Tax justice goes beyond tax, and, most importantly, encompasses tax havens too. Tax havens provide a crucial new analytic framework for understanding financial globalisation. Tax havens expand the debate beyond tax into the areas of financial secrecy, financial regulation, criminal law, accountancy, economics and much more.

Tax justice also refers to a growing global movement – the tax justice community – which we at the Tax Justice Network are proud to have contributed to and helped pioneer. As late as the mid 2000s, we still felt rather alone in pushing the agenda, helped by only a small group of others such as Citizens for Tax Justice in the United States. The world is fast waking up – and we now have a wide and growing range of allies.

Our analysis of tax havens has led us into many unexpected areas, and our body of work is growing into a complex, powerful and internally coherent worldview: a “Tax Justice Consensus” to challenge and replace the so-called Washington Consensus which has come to dominate economic thinking since the 1980s.

(Tax justice overlaps with ‘fiscal justice’. Fiscal justice involves both the revenue-raising and the spending side of the equation, but it tends to exclude the non-tax elements of offshore tax haven activity.)

What is the difference between tax avoidance, tax evasion and tax cheating?

The term “tax evasion” is usually taken to mean fraudulently under-declaring your tax liability. It is usually a criminal activity. Tax avoidance, by definition, is supposed to mean escaping tax by getting around (or avoiding) the spirit of the law, without actually breaking it.

But there is a large overlap between the two. In fact, a lot of what gets called ‘avoidance’ looks rather more like evasion: it involves pocketing tax money that legally should be paid. It’s just that they don’t get challenged or caught.

For example, BigCorp may aggressively exaggerate the value of goods and services passing between two subsidiaries, in order to shift as much profit as possible into a zero-tax haven. They have not operated in good faith within the law. An aggressive exaggeration may be as far form the truth as a plain lie.

Occasionally, a news organisation might even expose the shenanigans. But – whether it’s because BigCorp’s tax directors took the taxman out for an expensive dinner, or because the head taxman turns out to be terrified of annoying corporations, or is an anti-tax zealot, or the authorities are hopelessly outgunned by the armies of corporate lawyers – or, most commonly, they simply don’t have enough information to know they are being taken for a ride – the authorities still won’t challenge the arrangement. Almost all these schemes get away with it, and the schools and roads don’t get built.

And so BigCorp. will say: “We have not broken any laws.” Journalists may write “the arrangement was perfectly legal and legitimate.” Their readers sigh, and move on with their lives.

But this is likely to be false reporting. If a company has not been shown to have broken the tax laws, it does not follow that what they did was ‘perfectly legal.’ (Also remember: what is legal is not the same as what is legitimate: think Apartheid.)

To cut through all the nonsense here, focus on what matters: the economic and political aspects, not the legal ones. Whatever the legality of the arrangement, the result is fewer roads, schools or hospitals – and larger bonuses for wealthy corporate executives. A corporation is free-riding off the benefits paid for by others.

So rather than trying to work out whether the arrangement was avoidance or evasion, it is usually better to use broader terms such as tax dodging, tax cheating, or tax abuse.

If you’re keen to draw a line somewhere, sidestep the maddening distinction between avoidance and evasion, and focus instead on the difference between tax abuses and ‘legitimate tax planning’ (i.e. eliminating tax cock-ups where you pay more than you really should).

Read more about this here.

What are the four 'Rs' of tax?

The four “Rs” of tax refer to the main benefits that flow from taxation. They are:

- Revenue. Taxes raise money to pay for health, roads and education, or for more indirect things like good regulation and administration. But there is much more to tax than this.

- Redistribution. Tax can help reduce poverty and inequality, and spread the benefits of development more widely, by redistributing resources from those that can best afford it to those that need it most. Unfortunately, some tax systems redistribute wealth upwards, not downwards.

- Repricing. Taxes and subsidies can be used to change behaviour: taxing tobacco or carbon-based energy, for example, can be used to change behaviour and curb harmful practices.

- Representation. This is the least well known function of tax, but it may be as important as Revenue-raising. Tax strengthens and protects channels of political representation: when citizens are taxed, they demand representation in return from their rulers. This builds accountability, and the tax-raising imperative helps build responsive institutions.

What makes a good tax system?

Each country is different, and it is hard to make too many generic recommendations about what constitutes a good tax system.

Still, we take the view that, as general principles, populations are best served by progressive tax systems, which means that the wealthier sections of the population pay a higher effective rate of tax on their income and wealth than the poorer sections, which have less ability to pay since a larger share of their income is spent on necessities. We believe that a tax system should be broadly based across a range of taxes to achieve a variety of goals; and that capital tax rates should be aligned with those of higher income tax rates.

Many international organisations recommend that countries should cut tax rates on wealthier sections of the population and make up for the difference by ‘broadening the tax base’ – which means expanding things like Value Added Tax. We think there is a role for such taxes, in different contexts, but we urge extreme caution here: overly heavy reliance on them can have powerfully regressive effects.

Good tax systems should be as simple as possible, but no simpler. In a highly complex world peopled by armies of clever lawyers and tax accountants, a tax system that is too simple will be easy to escape.

Flat taxes are a gimmick, and a terrible idea. They are generally regressive, and their ‘flatness’ does little to simplify tax systems – progressive tax rates are not where the complexity is. Much of the complexity stems from defences put in place to tackle the schemes put in place by the enablers of tax avoidance.

We believe that Land Value Taxes are a particularly good form of tax, and should be a component of any good, broad-based tax system. Given the huge inequalities of wealth in this world, we strongly advocate wealth taxes too, including inheritance taxes. It is also crucial for any good tax system to have taxes that curb carbon use, other forms of pollution and other social ‘bads’.

We see the corporate income taxes as a particularly precious tax. There is a long-running, uncoordinated campaign underway to get corporate income taxes abolished. We very strongly disagree: among many other things, the more corporate taxes fall, the easier it is for wealthy individuals to escape tax by putting their assets into corporate structures. There are many other reasons to preserve corporation taxes: see here or here for example.)

For more on the purposes of tax, see also Alex Cobham’s document The Tax Consensus has Failed! and our FAQ on The Four ‘Rs’ of taxation.

"We need a competitive tax system! "

You hear this all the time. And it sounds so reasonable, doesn’t it?

The trouble is, using the language of ‘competitiveness’ to talk about national tax systems betrays a profound ignorance of the processes involved. The arguments routinely wielded about the need to be ‘competitive’ on tax are founded on bogus economics.

Competition between companies in a market bears no economic resemblance whatsoever to competition between countries on tax.

When government cut taxes on, say, multinational corporations, that means less money to spend on roads, education, the rule of law, and so on – or perhaps higher deficits and debts, or higher taxes on others, elsewhere. It is not at all obvious that such tax cuts make the country any more ‘competitive.’ And would any company site a car factory in, say, Somalia, if it offered a good enough tax break? Of course not. When multinationals look at locations to invest in, tax is almost always low on their list of priorities, below a healthy and educated workforce; good infrastructure; a reliable courts system; access to markets, and much more. These good things, by and large, require tax.

What is more, all the evidence shows that tax cuts have no discernible impact on long term economic growth. Very high-tax countries like Sweden have grown just as fast as low-tax countries like the United States or Japan. Which is hardly surprising, given that tax is not a cost to an economy but a transfer within it, from one sector to another. In fact, while the growth effect is neutral, it appears that high-tax countries seem to have significantly better human development outcomes than low-tax ones.

Read more about all this in a short article here, and explore these issues in more detail here.

Tax is too complicated for me!

Tax can be as complicated as you want it to be. But it doesn’t have to be complicated. Really.

For example, if you’re worried about transnational corporations cheating on their taxes, you don’t need to grapple with the often impenetrable complexity of their legal shenanigans, or even spend too much time thinking about whether they broke the law or not.

Tax justice tends to move away from the precise details of the artificial legal fictions that corporations cook up for themselves, and focus on the underlying economic and political issues: are they free-riding on everyone else? If Starbucks is paying close to zero percent corporation tax in Britain, while telling its investors how profitable its British operations are – then there’s an abuse and problem that needs pointing to and fixing – whether or not Starbucks broke the law or not.

These principles are very, very simple – and timeless. We’ve found that moving away from the legal arrangements and towards the economic terrain is very fruitful, and fit for protesters’ placards. And at the end of the day, it’s the economic argument that matter for ordinary taxpayers.

A lot of the fight for tax justice is about transparency. Again, secrecy structures to achieve secrecy can be complicated, but you don’t need to understand them to have something to think or campaign about.

And by focusing on tax havens, we get into a terrain that is at the heart of the global economy. Here, there is a huge range of different avenues that can be followed. Take your pick from, say, capital flight, corporate responsibility, secrecy, criminal activity, corruption, tax – and plenty more. If you’re daunted by the technicalities, just pick your area of interest and engage at a level that suits you.

There is something here for everyone. Have a browse around the ‘topics’ section of this site, and follow the links. And, if you like, take action.

Tax havens can’t be all bad?

Are tax havens not defenders of freedom and free markets?

Freedom for whom? For most of the world’s citizens, the exact opposite is true.

Tax havens, or secrecy jurisdictions, provide financial freedom to wealthy and powerful élites – to escape the rules of civilised society. This is the uncontrolled freedom of the fox in the henhouse: free for the fox – but not quite so free for the chickens.

What is more, many tax havens, and particularly the small ones where it’s easiest for financial interests to capture the policy-making apparatus, are in fact rather repressive places, intolerant of criticism. Read more about this here.

Do tax havens not protect vulnerable people from despots?

This is one of the most common and most alluring arguments used by defenders of tax havens. However, this argument almost entirely evaporates once it is properly examined. This is for several reasons.

First, it is almost always the most powerful and wealthy élites in a society that benefit from offshore secrecy. After all, who is more likely to use a Jersey trust with a BVI corporation and a Swiss bank account: the vulnerable street protesters on the barricades; the embattled human rights activists – or the despots and their cronies who are oppressing them? We all know the answer to that. Their ability to stash their looted assets offshore in secrecy,

Second, we have no problem with people in troubled jurisdictions sending their money or assets elsewhere for safekeeping. But there is no role for secrecy in this equation. If a citizen earns income on those assets elsewhere, they should still pay their taxes, and information should be shared appropriately. If the citizen hasn’t broken the law, their rulers will not be able to ‘confiscate’ their assets, even if information is exchange.

To a significant degree, it is the élites’ ability to hold their wealth offshore in secrecy that creates impunity, helping cause the governance problems in the first place. If there is an unjust law or bad government, then to provide an escape route for a small, wealthy and powerful elite – the only constituency with the political strength to drive reform – is to undermine pressure for change. Everybody else must then suffer in silence. Tax havens protect despots and help keep them in power.

There are in fact a range of other arguments that must be considered in response to this question. Explore this issue in more detail, here.

Tax havens have the sovereign right to set up their own tax systems

They do indeed. And other jurisdictions whose tax systems or criminal authorities are undermined by them have every sovereign right to take aggressive countermeasures against them, to co-perate to tackle the problems, and to criticise them.

Tax havens have competitive tax systems: that can't be bad

It sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? We must have a ‘competitive’ tax system! Competition is good, right?

But these arguments are nonsense, based on woolly thinking and fundamental economic fallacies.Despite sharing the same word ‘competition’ – tax competition between countries and tax havens is nothing whatsoever like competition between companies in a market.

Market competition is mostly a good thing – and tax competition is always a bad thing.

Think about it like this. When a company cannot compete in a market it goes bankrupt, and a better one takes its place. For all the pain involved, this “creative destruction” is, in general terms, a source of economic dynamism. But what do you get when a country cannot “compete?” A failed state? No. This kind of ‘competition’ is clearly a very different beast.

If there is a meaningful way in which countries compete, it is on things like good infrastructure, a healthy and educated workforce, the rule of law, and so on. All these things depend on raising tax: so it isn’t obvious, even in principle, that cutting taxes will make an economy more “competitive.” And for most businesses, these other good things matter more than tax rates when deciding where to invest. Would you site a car assembly plant in Equatorial Guinea just because it gave you a tax break?

And there is another thing. Take this sentence “Tax competition forces governments to cut taxes.” Now unpack that. This word “forces” says it all. Governments are elected by their people to look after the public interest. When they are “forced” to act differently, this undermines democracy and accountable government. And what applies to tax applies to financial regulation, safeguards against criminal money, and much more besides.

In short, the arguments in favour of tax competition are bogus. Read much more about this here.

'Tax havens are just tax-neutral conduits for efficient finance'

This is one of the commonest arguments wielded by tax havens, and one of the most deceptive.

It is true – as we have repeatedly noted – that tax havens serve as conduits for flows of international trade and investment. But that is not to say that this is how the global economy should be organised.

Transnational corporations (TNCs) use these offshore conduits substantially as tax-free or tax-light pathways through the global economy. Helping TNCs dodge tax may seem ‘efficient’ from a TNC’s point of view, but anyone who says that such practices are ‘efficient’ from an economy wide-view is committing an elementary economic howler: confusing the fortunes of the corporate sector with the fortunes of the wider economy. If a boost to one part of the economy comes at the expense of another part, then it is simply wrong to conflate the two.

These conduit arrangements are created and used with the stated purpose of avoiding ‘double taxation’ (see the other FAQ) but in fact what these conduits so often do is create something entirely different: double non-taxation, via such shenanigans as the “Double Irish” and “Dutch Sandwich”.

Essentially, these conduits regularly serve as pathways from supposedly ‘onshore’ economies into a much less regulated and less heavily taxed world of potential shenanigans, away from the gaze of regulators supposed to protect their populations and their tax systems.

Read more about all this in our ‘tax treaties’ page, and see top U.S. tax expert Lee Sheppard on this slippery topic. See also this IMF report noting acerbically that these claims in tax havens’ defence are “essentially uninformed by empirical knowledge.”

Do tax havens not make global markets more efficient?

Tax havens corrupt and distort global markets, and make them more opaque. They distort markets and make them less efficient. This happens on multiple levels.

- One of the common weasel words in the offshore lexicon is “tax efficient.” It sounds good – but what does it mean? It means ‘efficient’ from the (usually wealthy) tax avoider’s point of view. Yet someone else, somewhere else, has to pay the taxes they won’t. The end result is one set of rules for the rich and powerful, and another set for the rest. There is nothing efficient about that.

- Tax havens are, as they often say, nimble and flexible, and in one sense are very ‘business-friendly’. But what do “nimble” and “flexible” mean here?. In the offshore context, ‘flexible’ means that if a country elsewhere has rules against something, tax havens will flexibly find ways to help wealthy people escape those rules. Whatever the warts and failings of those rules – tax laws, inheritance rules, financial regulation, and so on – they are usually put in place for good reason, as part of society’s democratic bargain. If a jurisdiction said “we have a flexible approach to crime” – we don’t care if you are breaking someone else’s criminal laws – this is not ‘efficient’. In fact, the business model of tax havens is built around this kind of ‘flexibility’.

- Tax havens may look ‘efficient’ from the perspective of an investor or company. But if we are considering whether tax havens are beneficial for the world’s economy, this is the wrong perspective. It is essential to consider the question from the point of view of the system as a whole. Bribery is “efficient” from the point of an individual company that wants to win a contract, or get its container quickly through a port. But that does not mean bribery is “efficient” in general terms: quite the opposite, in fact.

- Rules, laws and taxes are required if markets are to be efficient. But tax havens can provide escape routes from those rules, laws and taxes.

- Tax havens distort markets. For example, by facilitating offshore tax avoidance they effectively provide tax subsidies to transnational corporations (TNCs) that give them advantages over their smaller, more locally-based competitors. This enables TNCs to kill their smaller competitors in markets on a factor – tax – that has nothing to do with genuine economic productivity or the quality of their goods and services. As smaller firms are squeezed out, oligopolies and monopolies are reinforced, raising prices. Since smaller firms tend to be the genuine innovators and job-creators, this creates a wide range of economic and political harms.

- Tax haven incentives help company managers focus on tax and regulatory avoidance which frequently means they take their eyes off doing what they do best: making better, cheaper and more innovative products or services to supply to markets.

- Billions of dollars are spent annually by corporations on tax and legal advisers to cook up complex avoidance schemes to fox the tax, criminal and regulatory authorities. This is a waste of resources and involves a tremendous opportunity cost – those are some of the world’s most highly educated minds that could have been put to use in genuinely productive fields.

- Tax havens promote and create secrecy. Efficient market theory rests on an assumption that markets are, in the jargon, “informationally efficient.” Offshore secrecy works directly and aggressively against this: it helps information to flow only to insiders, helping them earn excess returns. Finance and trade flow freely around the world; the information that needs to accompany it is blocked.

- The offshore system has helped financial sector actors escape and undermine financial regulations: see more here, for instance.

- By providing benefits that are almost always available only to the wealthier sections of society, tax havens make societies more unequal. The “nimble and flexible” regulatory environments offered by secrecy jurisdictions, and the ‘tax efficient’ escape routes they provide, protect the interests of insiders against wider sets of stakeholders.

- By helping wealthy corporations and individuals escape tax, whether legally or not, tax havens help them free-ride off society, taking its benefits such as healthy and educated workforces, the rule of law and good infrastructure, while getting others to pay for those benefits. This is profoundly subversive of democracy and the rule of law.

- The offshore system creates impunity for elites in developing countries and helps dictators stay in power. Their secrecy facilities have made them a gigantic global hothouse for crime, mafia activities, drugs smuggling, insider trading, corruption, bribery and even terrorist finance.

- These élites in developing countries have often captured the proceeds of international borrowing, stashed their loot offshore, then left ordinary taxpayers and users of government services to pay for the resulting external debt service. The result has been, time and again, financial crisis after crisis.

All these impacts distort markets and society, boost economic and political inequalities, and undermine governance.

It is hard to see how any of this is “efficient.”

Can tax havens clean up their image?

They can stop being tax havens, of course. But to understand the basics of this subject, see this.

Taxing Corporations

Do company directors not have a duty to avoid tax?

Do corporate directors have a duty to their shareholders to avoid tax as far as possible within the law?

The answer is no: absolutely not.

This is certainly true in the United States and the United Kingdom – and indeed we have obtained a formal legal opinion in the United Kingdom stating just that (see also here). The all-important Delaware courts in the U.S. have also ruled that “there is no general fiduciary duty to minimise taxes.” (In most other countries, this will also be true, though we haven’t conducted an exhaustive survey.)

Company directors generally have duties to promote the success of their companies. But in doing so, they are required to consider a wider set of stakeholders than merely shareholders: they need to balance the interests of their shareholders against the interests of wider society. That gives them wide leeway to decide how far to push the envelope as regards tax avoidance.

In general, payment of tax needs to be part of companies’ corporate responsibility offerings. See much more on this on our permanent Corporate Responsibility webpage.

Is tax a cost?

From a company’s perspective, tax may seem like a cost. But from a society’s point of view, it is not a cost but a transfer. So there is no obvious reason from the outset why any kinds of tax cuts should make any economy more ‘competitive.

Yet even from a company’s perspective, a corporate income tax is not in fact a cost. It is a distribution to society, out of profits.

This puts tax in the same category as a dividend: a return to the stakeholders in the enterprise. This reflects the fact that companies do not make profit merely by using investors’ capital. They also use the societies in which they operate – whether the infrastructure provided by the state; the healthy and educated workforces; or the rule of law that protects their property rights and contracts.

Tax is the return due on this investment by society from which companies benefit. See more on this here.

"Don't blame corporations. Governments must change the tax system!"

This is one of the commonest claims we hear: that corporations should not pay more than they have to, so there is no point complaining when they dodge tax. Governments must simply fix the tax laws. Leave corporations alone!

It is another one of those alluring arguments which falls apart under examination.

First, consider the process here.

Accountants and corporations dream up new tax schemes, often via tax havens. Governments put in place defences against those dodges. The accountants concoct new wheezes to get around those defences, and the corporations buy into those schemes. Governments try to patch up the new holes . . . and so on. The tax system steadily just gets more and more complex. This is tough enough for rich countries: it is impossible for under-resourced poorer ones.

The companies work actively to create and exploit holes in the law. In many cases, they also lobby, in some cases so unashamedly that they effectively write the laws for themselves.

So while we certainly do need to hold governments to account on tax – it is essential also to hold corporations’ feet to the fire. They are a central part of the problem.

Second, It is not a question of a corporation simply saying “here is the x% effective tax rate, which is the minimum we should pay, and then we can volunteer to pay more if we like.” Not at all. Many of them figure out ways to right down to zero (and sometimes even below): it is a question of how aggressive they want to be.

There is often a large grey area between tax avoidance (which is, by definition, not illegal) and tax evasion (by definition, illegal) and one usually doesn’t know for sure which side of that equation a corporation is on until the tax authorities have taken them to court and obtained a resolution. (In fact, it is even worse than this, as this blog explains.)

The more aggressive the tax strategies, the deeper they push into the grey area. There is no law or even guidance, anywhere, that tells corporate managers how aggressive to be. They don’t even have — contrary to many assertions — any duty to their shareholders to avoid tax.

So corporations and their bosses have a genuine choice: are they going to design their tax strategies according to what is economically reasonable, or are they going to get aggressive and free-ride off others as far as possible? (For further subtle arguments, also see this. )

So public opinion, and public pressure, has to an important role here. Public pressure to change the climate of opinion about tax dodging – and particularly pressure on specific companies – will lead companies and their directors to make more economically justified choices: perfectly reasonable choices within the law and within directors’ duties. This is not a question of making voluntary tax contributions.

What is more, plenty of research shows that those managers who focus on genuine wealth creation rather than on short-term wealth extraction through tax avoidance (and other mechanisms) tend to win out in the long run.

What is transfer pricing?

Transfer pricing is one of the most important issues in international tax.

Perhaps half of all world trade happens across borders inside transnational corporations (TNCs). When different affiliates of the same TNC trade with each other, they set those internal transfer prices to suit them. By adjusting these prices, they can artificially shift profits out of high-tax countries into low-tax ones, and shift their costs into the high-tax countries, to cut their tax bills.

For example, it costs a multinational corporation $100 to produce a crate of bananas in Ecuador. It sells that crate to an affiliate in a tax haven for $100, leaving no profits in Ecuador. The tax haven affiliate immediately sells that crate on to an affiliate in Poland for $300, leaving $200 profit in the tax haven. That Polish affiliate sells the crate at the genuine market price of $300 to a supermarket, leaving no profits in Poland.

Hey Presto! The multinational has paid no tax in Ecuador, and no tax in Poland – and has shifted $200 in profits to a tax haven, where those profits don’t get taxed!

It is obvious that nothing of economic substance has happened here: this merely involves changes in accountants’ workbooks, resulting in a transfer of resources away from ordinary taxpayers and towards wealthy (and usually foreign) shareholders – typically in a foreign country.

Clearly, the real world is more complex than this: countries put in place defences against these abuses. But those defences are always leaky and subject to attack by lobbyists, leading to new kinds of shenanigans. Which provoke new responses – and tax systems grow ever more complex.

For more on transfer pricing, see our Taxing Corporations page.

What is unitary tax?

Unitary taxation is a way of taxing transnational corporations (TNCs) according to the genuine economic substance of what they do and where they do it – rather than the dominant current system where they are taxed according to the artificial legal forms that their accountants contort them into. This system is economically just and far more efficient – and already working successfully in several places.

Currently, the dominant international tax system treats a TNC as if it were a loose collection of independent entities all trading with each other in a free market. This opens the door for endless abuses, as it gives TNCs tremendous scope to use transfer pricing and other tricks to shift profits into affiliates in favourable jurisdictions to escape tax.

But under a unitary tax system, you take a TNC’s total global profits, then allocate the profits to the countries in proportion to where it does its genuine business – using a formula based on real economic factors like sales, payroll or physical assets. This treats TNCs like unitary wholes, rather than as loose collections of separate entities trading with each other – and it completely ignores the internal transfer prices with which they trade with each other. You don’t need full international co-ordination for it to work, though co-ordination helps.

For example, imagine a company with 10,000 employees in Sweden, 10,000 employees in Tanzania, and two tanned accountants throwing paper aeroplanes in an office in Bermuda. Under current rules, the profits are all shifted to Bermuda, which doesn’t tax them. So it gets taxed nowhere. But under unitary tax, you would take the company’s global profits then allocate nearly 50 percent to Sweden, nearly 50 percent to Tanzania, and almost none to Bermuda. Each country can tax its portion of the global profits at whatever rate it likes.

Under this system the Bermuda operations would make almost no difference to its tax bill – so TNCs would not bother setting up many offices in tax havens.

With a unitary tax system we would see the tax havens’ most loyal and powerful supporters melt away – and the havens would be far easier to tackle on a host of other issues such as secrecy and international crime.

"Don't tax or regulate them too much or they will flee to Zurich or Hong Kong!"

We hear this one all the time. And in the face of this threat, we see politicians the world over quailing, and giving the financiers what they want.

But there are three very powerful reasons why these cries should pretty much always be ignored.

First, talk is cheap. It is easy to make this threat. But the number of rich people or corporations who actually do up sticks, rip their (or their employees’) children out of schools and relocate to other countries is always miniscule when compared to the number of threats that are made. As Warren Buffett put it:

“I have worked with investors for over 60 years and I have yet to see anyone shy away from a sensible investment because of the tax rate on the capital gain.”

What real businesses want are good things such as the rule of law, a healthy and educated workforce, or good infrastructure. All these things require taxes. So when politicians order taxes to be cut in response to these threats, they are doing it not because of hard economic realities, but because of a false belief system that has grown up, fostered and encouraged by the world’s biggest corporations and their associated lobbyists.

A second reason not to give in to the threats is that those businesses that are most likely to flee at the prospect of tax hikes are those that are most footloose and – by definition – have least connection with the local economy, and will create few or no jobs. They are precisely the ones that won’t be missed. They are also the most likely to be involved in unproductive rent-seeking and unproductive wealth extraction, in contrast to the genuine value creation that genuine businesses get involved in. What is more, the lost taxes paid by them – not to mention the many other businesses that had no intention of fleeing but will benefit from those tax cuts anyway – will be sorely missed.

A third reason is that when there is a good economic opportunity in a country – an oilfield, say, or a licence for telecommunications spectrum or for operating a supermarket chain, this opportunity will typically have several suitors. On the rare occasions where one investor decides not to get involved purely for tax reasons, that is unlikely to be a major problem: the oil is there, and others will come to exploit it – and likely on better terms than if the country had given in to the departed company’s demands for subsidies.

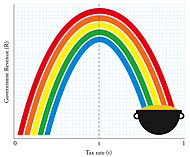

What is the Laffer Curve?

For tax-cutting politicians, the Laffer Curve is the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

In short, the idea is that if you cut taxes this will create such an explosion of economic dynamism and reduce tax avoidance so greatly that tax revenues will ultimately end up higher. It is the ultimate political free lunch.

The idea became popularly known as the Laffer Curve in the 1980s when a little-known economist called Arthur Laffer drew his theory in the form of a graph on the back of a napkin for Dick Cheney, who would later become U.S. vice-President. Cheney led the charge in popularising it.

If you plot a graph with tax rates on one axis, and tax revenues on the other, you will theoretically get a curve, as in the picture. At zero tax rates, you will get no revenue. At 100 percent tax rates, the theory goes, you will also get no revenue, because nobody will do any work. In the middle is the ‘sweet spot’ of maximum revenue.

This graph’s simplicity and elegance has bamboozled legions of politicians – and even a few economists. In the face of all the evidence that tax cuts seems to have no impact on growth, it is now regarded as a laughing stock among economists. Greg Mankiw, former chairman of George W. bush’s council of economic advisers, called its adherents “charlatans and cranks.” President George H.W. Bush called it ‘Voodoo Economics.”

Read more about the Laffer Curve and its history in the New York Times, or in the New Statesman.

Who bears the burden of the corporate tax?

There is an army of lobbyists out there arguing that corporate income taxes are ultimately borne by the poor workers, so it isn’t a progressive tax. This is sometimes known as the tax ‘incidence’ argument. It’s nonsense: as with so many arguments we encounter it rests on unworldly models standing on ridiculous assumptions.

Those who have actually done the hard research find that the corporation tax falls squarely on the shoulders of the wealthy owners of capital. See more here or here or here or here.

What does tax justice have to do with . . . ?

What does tax justice have to do with human rights?

When dictators loot their countries and stash their winnings in offshore tax havens, the human rights implications are potentially enormous.

And there is plenty more. See our dedicated web page on this topic, here.

What does tax justice have to do with corruption?

Tax havens, or secrecy jurisdictions, provide secrecy. The offshore system of secrecy jurisdictions clearly provides a criminogenic environment that facilitates all manner of corrupt practices.

But this is merely the beginning of the story. For more on this, see our web page dedicated to tax justice and corruption.

What does tax justice have to do with inequality?

In a word, everything. Read more here.

What do tax havens have to do with the financial crisis?

To understand how the offshore system contributed to the crisis, it is essential to understand first what a secrecy jurisdiction (or tax haven) is. First, the biggest offshore players are not so much the Caribbean islands or wealthy Alpine nations, but are big powerful nations such as the United Kingdom. Second, tax havens are about much more than tax. It is necessary to understand the core tax haven business model: to get rich by offering wealthy individuals and corporations escape routes from the laws, rules and regulations of democratic societies elsewhere.

Offshore tax havens offered a “get out of regulation free” card to banks and other financial firms and served as the secret battering rams of global financial deregulation. Read about this in Treasure Islands, particularly the “Ratchet” chapter.

By providing an offshore playground where banks could get around reserve requirements, restrictions on investment banking, and other parts of the social contract — and by puffing them up further with massive profits from secrecy-driven private banking — they helped major global banks grow far faster than their onshore competitors: eventually becoming too big to fail.

By playing the offshore card – “don’t regulate us or we will go to Switzerland!” – financial firms forced politicians to capitulate to their demands. So financial institutions became not only too big to fail, but also too hard to control and regulate.

The secrecy jurisdictions also served as conduits for massive illicit financial flows from poor countries to rich ones. These illicit flows, estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars per year, added to the more visible global financial imbalances between countries that many economists blame for the crisis.

Corporations began to festoon their financial affairs through offshore jurisdictions for all kinds of reasons: for secrecy, for lower taxes, to escape financial regulations – and this generated massive complexity in their affairs. When crisis hit, nobody could work out what was going on. Offshore secrecy then helped them conceal their losses.

Corporations, and especially financial corporations, had offshore incentives to load up on debt: while income from lending racked up offshore, tax-free, the borrowing costs – the other side of the same equation – were charged against earnings onshore in the countries where most of us live – and thus deducted against tax. This debt-loading added to the crisis.

And now – as if all that were not bad enough – the offshore system continues to help wealthy individuals and corporations shake off their tax burdens, undermining nations’ collective ability to pay for the gigantic mess they have created.

Read more on all this here:https://www.taxjustice.net/cms/front_content.php?idcat=136

What do tax justice and tax havens have to do with banks?

Conservative estimates put the total amount of money stashed offshore, beyond the reach of effective taxation, at $21 to 32 trillion. That is Trillion, with a ‘t’.

That many dollar bills, laid end to end, would stretch several times along the orbit of the earth around the sun.

Clearly, the offshore has moved far beyond the quaint notion of hundred-dollar bills being moved across borders in attaché cases by bearded men wearing sunglasses.

The offshore system is all about banks.

Every multinational corporation has affiliates in tax havens – but in survey after survey, banks have been found to have by far the largest number.

They are typically not just passive recipients handling dirty money, but in many cases actively and aggressively courting it, to be the recipients of as much capital flight as possible. They are some of the most important private enablers of the offshore system.

What does tax justice have to do with 'competitiveness'?

Everything. Here lies one of the great misunderstandings in economic debates. For an introduction to these issues in the area of tax, see our Mythbusters document: A competitive tax system is a bad tax system.

For more on this enormous subject, also see this blog, as well as our Finance Curse page and our Race to the Bottom page, which explore issues beyond tax, including what it means to be ‘competitive’ on financial regulation.

What does tax justice have to do with morality

This is a big question, with no simple answer. As David Quentin notes, however, there are some very simple ways to view this question:

There remains a completely pointless semantic/philosophical debate over whether tax abuse is “immoral”, but that debate could be eliminated by replacing the word “immoral” with the word “anti-social”. There is now a rock-solid consensus that abusive tax behaviour is anti-social

http://dqtax.tumblr.com/post/101481029671/people-talking-out-of-their-asset-classes

We wouldn’t say that the debate is entirely pointless, but we agree with the rest of it.

A theologically-grounded study of the question of corporate tax avoidance notes:

“Many developing nations are seriously affected by the way in which some multinational companies manipulate their profits to allow them to pay little or no tax in the countries in which they are operating. As Esther Reed observes in her paper, this simply feels wrong to most people.”

The morality of taxation goes far beyond narrow questions of legality.

Read more here https://www.taxjustice.net/2014/11/03/good-companies-may-pay-tax-law-requires-say-theologians/

Financial Secrecy

What are the different 'flavours' of financial secrecy?

Financial secrecy is different from legitimate confidentiality. A bank won’t publish your account details on the internet, in the same way that a doctor won’t hammer details of your ailments on the surgery door. Financial secrecy occurs when there is a refusal to share this information with the legitimate authorities and bodies that need it – for example to tax citizens appropriately, or to enforce criminal laws. Financial secrecy is harmful. Its comes in various flavours, which fall into three main categories.

The first is the best-known: plain vanilla bank secrecy – such as that offered by Switzerland. Bankers promise to take their clients’ secrets to the grave, and criminal penalties often apply to those who break the secrecy.

A second group involves permitting the creation of entities and arrangements – whether corporations, trusts, foundations or others – whose ownership, functioning and/or purpose is kept secret, and sometimes where the very legal basis of ownership becomes muddied. These structures can hold many assets – yachts, shares, Swiss bank accounts, luxury London properties, and so on. Secrecy provided through an offshore trust, for instance, can be even harder to break than bank secrecy (read more about trusts here.)

The third general mechanism of secrecy involves jurisdictions putting up barriers to co-operation and information exchange. This may be achieved either through an unwillingness to share information with other jurisdictions, or deliberately refusing to pursue and collect information held locally, so that even if they have impeccable information-exchange agreements, they don’t have the information available to share. Many jurisdictions also make a business model out of selective non-compliance with their own laws.

Our Financial Secrecy Index breaks down financial secrecy into 15 indicators grouped under the above three headings: explore those here. See also our permanent webpage The Mechanics of Secrecy, which provides links to a range of documents exploring this issue.

How do trusts work?

Trusts are one of the most important mechanisms used in modern global finance. They can have legitimate purposes, but they have many illegitimate uses too.

A trust typically involves three main parties. One party (“the settlor”or grantor or donor) — typically a wealthy person, hands an asset to a trusted second party (“the trustee”), for example a lawyer (or a dedicated trust company) — who in turn control the property on behalf of a third party (“the beneficiary”) who might be the settlor’s child, for example.

In theory, the settlor is supposed to have genuinely given away the asset. This already creates the potential for a secrecy barrier: if the settlor no longer owns the asset, then it can be very hard to find any link between them and the asset.

But in practice, trusts can be extremely slippery mechanisms for manipulating the different attributes of ownership and control. Although the settlor has supposedly been separated from the asset, they may still through devious side measures (such as a secret ‘letter of wishes’) retain a measure of control over the asset, or have the power to enjoy its income or other benefits. They may, for instance, manage to get their hands on the asset’s income through a loan (that is never repaid) or a fee. Tax havens specialise in facilitating this kind of complex skulduggery. Discretionary trusts, which are especially good at this kind of manipulation, are especially common types of offshore trust, and they alone are responsible for trillions of dollars’ worth of assets sitting in a kind of ‘ownerless’ limbo.

For a fuller explanation of how trusts work, see our longer blog In Trusts we Trust.

Frequently Asked Questions

For a glossary of terms, click here.

For a long list of tax justice quotations, click here.

Feel free to suggest others, via our contacts form.

Do something!

I want to DO something about this!

You don’t have to be an expert at all. Taking action is SO easy.