Poker cards from the London School of Financial Activism: a present to John Christensen to celebrate TJN’s 10th birthday.

This article provides an informal history of the Tax Justice Network (TJN) and the global tax justice movement, from our perspective. TJN’s early history is quite substantially British, but we have grown to become a truly international organisation. TJN itself was first triggered by a phone call from an impoverished Jerseywoman, Pat Lucas. But it has long antecedents.

The account that follows comes substantially from the perspective of TJN’s Director, John Christensen, who is first among equals in our founding, and its leader since the beginning.

TJN’s pre-history

People and organisations have stood up for tax justice for decades: even centuries. Our Offshore History page highlights some of the antecedents described here — whether Citizens for Tax Justice in the U.S.; early fighters against tax havens such as Eva Joly or Jack Blum; more recently tax writers Richard Brooks or David Cay Johnston; or the Uncut movement against corporate tax avoidance and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) with its massive recent exposés of tax haven activity in the Panama Papers, Luxleaks scandals and more.

TJN and its many associates around the world can claim credit for playing a central role in the creation of a coherent intellectual framework for understanding tax havens: a new framework for understanding financial centres and financial globalisation. Our analysis is steadily sweeping the globe, and has had great influence — as others attest.

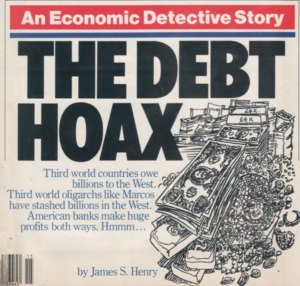

Some of TJN’s Senior Advisers were active long before TJN existed as an organisation. They include Jack Blum – a veteran U.S. lawyer who was instrumental in breaking the Lockheed Martin scandal in the 1970s, in investigating General Noriega’s drug trafficking, and in bringing down the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI,) one of the most outrageously corrupt banks in modern history. Another early thinker was James Henry, a former Mckinseys Chief Economist who began investigating the looting of developing countries via western banks and tax havens, way back in the 1970s. See his seminal 1986 article in The New Republic, entitled The Debt Hoax, and his 1989 Washington Post article America the Tax Haven, two quintessential pieces of tax justice research that were years ahead of their time.

Some of TJN’s Senior Advisers were active long before TJN existed as an organisation. They include Jack Blum – a veteran U.S. lawyer who was instrumental in breaking the Lockheed Martin scandal in the 1970s, in investigating General Noriega’s drug trafficking, and in bringing down the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI,) one of the most outrageously corrupt banks in modern history. Another early thinker was James Henry, a former Mckinseys Chief Economist who began investigating the looting of developing countries via western banks and tax havens, way back in the 1970s. See his seminal 1986 article in The New Republic, entitled The Debt Hoax, and his 1989 Washington Post article America the Tax Haven, two quintessential pieces of tax justice research that were years ahead of their time.Yet in general, the kind of information needed to properly understand the fast-growing offshore world was almost entirely absent from the public domain. Christensen was involved in investigating tax haven-related corruption in Malaysia when working there in 1985, and resolved at the time to explore the issue more fully. This is described in Treasure Islands:

He went to Britain, where he spent a couple of months combing libraries and seeing all the economists and capital markets experts he could find to try and understand where the money went and how the offshore system worked. Nobody knew anything.

“I don’t think anyone had understood how malevolent this thing had become,” he said. “There was no useful information anywhere.”

Christensen cites Sol Picciotto‘s 1992 seminal book International Business Taxation, now available as a free download, as being “the book that crystallised a lot of my thinking,” notably on the all-important issue of tax havens and corporate tax avoidance. There was also, however, an accounting expert at Essex University, Prem Sikka, who was also publicly speaking out on these issues, and in 1998 he launched the Association for Accountancy and Business Affairs (AABA,) and its seminal publication Auditors: Holding the Public to Ransom.

Ronen Palan, author of books such as the 1998 publication “Trying to Have Your Cake and Eating It: How and Why the State System Has Created Offshore,” was another early influence. All the above are Senior Advisers to TJN today. Susan Strange, a British academic who looked at tax havens and financial instability through a similar lens, and whose work inspired many who have worked with us, passed away before TJN was born.

Outside of TJN one might also point to the work of Prof. Mark Hampton and particularly his 1996 book The Offshore Interface, as being influential in this area, at a time when there was almost no intellectual framework – anywhere in the world – for understanding tax havens. In the United States, Citizens for Tax Justice (not organisationally related to TJN, but good friends of ours) and their indefatigable leader Bob McIntyre have for decades played a crucial role in addressing tax justice issues inside the United States, and although their occasional forays into the difficult world of international tax havens only went so far, their influence in the U.S. on issues of tax fairness has been unparalleled. A seminal book on Ronald Reagan’s great tax reform of 1986 remarked:

“In the tax debates ahead, Bob McIntyre’s one-man report would turn out to be more influential than all the firepower the corporate lobbyists could muster.”

Elsewhere, with a more international outlook, work by Unctad, and the OECD in the late 1990s with their ill-fated Harmful Tax Competition project, was complemented by the work of the UN economist Vito Tanzi, who in 2001 aptly referred to tax havens as “fiscal termites“. Tanzi played an important role in the UN Financing For Development conference in Monterrey, Mexico in 2002 and the resulting “Monterrey Consensus” that emerged was ahead of its time in that it called – at a time when almost nobody else was doing so – for developing countries to shift their focus away from aid and borrowing, and looking more to mobilising domestic resources – that is, tax — to finance their development.

Despite the Monterrey Consensus being widely reported on, there was still no decisive shift in the global zeitgeist. Tax was still generally to be avoided and was ‘bad for growth’ (still reflected in the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business’ country reports), the consensus held that tax havens were either exotic, somewhat irrelevant sideshows to the global economy, or ‘efficient’ neutral platforms for whooshing large quantities of money around the world. An attitude of see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil prevailed in Washington, Brussels, Paris and London.

In 1996 Prem Sikka went to Jersey to research a particular legislative process (involving a Limited Liability Partnership law, which he later would describe in Chapter 6 of his 2002 monograph No Accounting for Tax Havens.) That’s a fascinating political economy story in itself, and both publications have contributed significantly to making the arguments available to non-specialist audiences. During his research in St Helier, Jersey, he first met Christensen, who was then Economic Adviser to the tax haven, but something of a dissident towards the offshore financial sector there. Straight away, the intellectual sparks began to fly. It was to prove a crucial meeting. Christensen remembers:

“After just a few hours of discussion, clandestinely in a bar in Saint Helier, he had convinced me that the time was ripe to move on and start to campaign against tax havens.”

Christensen quit his job (and Jersey) in July 1998 and went to work in the private sector in London, while nurturing plans to set something up. In 1999 he advised the charity Oxfam on their seminal June 2000 report, Tax Havens: Releasing the hidden billions for poverty eradication, which stimulated some interest at the time but not enough: many non-governmental organisations in those days were overwhelmingly focused on how to increase aid levels, rather than on the tougher but more important question of how developing countries could mobilise their own revenues. “This just wasn’t on the radar screens,” Christensen said.

In September 2002, he received a call from a Jerseywoman he had never heard of, Pat Lucas. She said she had heard him and Hampton speak in Jersey and wanted to visit him to discuss various issues. He invited her to his house in Chesham, and she flew over with two friends – Jean Andersson and Frank Norman. Over tea and cakes the three Jerseyfolk pleaded with Christensen to “rescue our island” from the offshore industry that had grown up all around them and causing great local harm (see more on what that’s all about, here.) Andersson recalls:

As we sat in John’s office he asked us “What do you want to do?” And if I remember rightly Pat answered; “Get rid of the Tax Haven!”

Christensen continues:

“They were talking about liberating the island. I said that if you want to do that, you have to take on the entire issue of tax havens and the global economy. They grasped that pretty fast, and asked: ‘if that is what it takes, how do we set about doing that?’ I said that we will have to create a mammoth global campaign to raise public awareness. It was clear to me by the time they left, three hours later, that this was the call to arms. I knew instantly that this was what I had been wanting to do.”

The three visitors to Chesham invited Christensen to a meeting in Jersey entitled Tax Havens and Globalisation, on October 12th, 2002, organised by the Attac Jersey, a local organisation linked to Attac in St. Malo, France. Attac Jersey had been one of the only ones to have protested against the tax haven industry in Jersey. Christensen immediately called Sikka, who said “count me in” – but also advised that he had come across an accountant whom John had not yet heard of, called Richard Murphy. They invited him to join. This conference, still before TJN’s formation, was another seminal moment in TJN pre-history. For the record, the programme was as follows (click to enlarge):

Christensen recounts:

“This was the first time I met Richard and, bizarrely, within minutes of meeting we were discussing the need for country level disclosure of transnational company accounts: the idea of Country-by-Country (CbC) Reporting – the term came from Richard – was born in Jersey, of all places.”

The concept underlying CbCR had been pushed by Raúl Prebisch of UNCTAD in the 1960s, as a way for developing countries to get more granular detail about the accounts of western multinationals, to better detect profit-shifting. But the concept never got anywhere. Murphy went away and developed and wrote the first CbC accounting standard and has led the charge on country-by-country reporting in the ten years since then. It is an unarguable concept that is now spreading around the world.

It has since been a hallmark of TJN to push for the unthinkable – such as automatic information exchange, which we began pushing not long after we launched country by country reporting, with particular help from David Spencer and Michael McIntyre – and to steadily ‘change the weather’ up to the point where the ideas become accepted. (Our proposals were ridiculed at the outset: now they form the backbone of the OECD’s global standards.)

That conference, via an activist called Matti Kohonen, led to an invitation to another conference at University College, London, which culminated in an invitation from the NGO War on Want and Stamp Out Poverty to take a delegation to the European Social Forum in Florence. A delegation of Christensen, Hampton and War on Want’s Pete Coleman went, and joined with Bruno Gurtner from Switzerland, then time senior economist of the Swiss Coalition of Development Organisations; and Sven Giegold of Attac in Germany (who was very influential in the discussions and is now a highly influential European MEP.) This was the nucleus of the TJN founder’s group, and it was at that meeting, on 9th November 2002, that the name Tax Justice Network was chosen, TJN was officially formed, and the bare bones of an eventual Tax Justice Declaration were sketched out. A full list of TJN’s founders is available here.

TJN is launched

TJN was officially launched in the British Houses of Parliament in March 2003: the crucial trio of Pat Lucas, Jean Andersson and Frank Norman were all there. Click to enlarge this wonderful archive photo.

At first, it was hard going. Clearly the new network would need a secretariat, but such was the apparent obscurity of the tax haven issue in those days that none of the founding organisations was able to put up a sizeable contribution to fund it.

Then good old Jersey intervened again. The Attac network there set to work organising boot fairs, local events and more to cobble together enough many thousands of pounds to get things started. We still don’t know just how they did it – but they did. And at that point, things began to get a little easier.

The Tax Justice Network formally launched its International Secretariat in September 2004, garnering its first major international newspaper headline, in The Guardian: Havens that have become a tax on the world’s poor, with some useful supportive commentary from UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

Yet it was still hard to get people interested. Christensen and the highly energetic and effective Sony Kapoor (now head of the think tank Re-Define) visited innumerable international conferences and events, while Sikka, Murphy and others beavered away with research. All talked to anyone who would listen – which, in those days, wasn’t that many. Christensen recalls what it was like:

“Our approach was to use beserker tactics, turning up at conferences and asking awkward questions. I remember one really embarrassing conference, where the chief executive of a leading development NGO came up to me and said ‘I really don’t understand what tax has to do with development.’

In fairness, she changed her position fairly soon. But this gives an idea of the steep wall we faced. Development NGOs aligned largely with corporates and governments: I have no problems with that, but their focus was on acting as aid delivery agencies, rather than on tackling systemic poverty. TJN is all about ‘how do we move beyond aid, so governments can deliver public services without debt — particularly external debt — and external aid?”

He also recalls one particularly difficult meeting at an international meeting on Corporate Responsibility at Chatham House in 2004, where he stood up to talk about the need to inject the dreaded word ‘tax’ into the corporate responsibility debate.

“We’d been ploughing through their Corporate Responsibilty statements, pressed the search button for “tax” and it didn’t come up. I said ‘I love the statements on best practice – but there is no mention of tax. None of you take acount of what we regard as primary CSR: how you contribute financially to societies in which you operate?’ I referred to it as the ghost at the feast: we we regard tax as the first responsibility of a socially responsible statement.’

They looked me as if I’d left a dog turd in the middle of the table. When I sat down it felt like there was a 30 second silence. My knees were trembling, my blood was pounding, and I could see that the chairman was utterly hostile.”

From around 2004 onwards, bit by bit, the issue slowly began to get traction, notably with non-governmental organisations, but increasingly with unions and then professional bodies. Still, even natural allies took quite some persuading: Sikka remembers visiting one trade union body in 2003-4, and finding that “they were simply not interested, because it was a little bit outside the box of traditional trade union interest.”

But, bit by bit, we noticed lights beginning to go on, in people’s heads, in all sorts of different fields. The world, slowly, began to wake up to the perils of tax havens, and the solutions. And we continued to push novel ideas, then encouraging others to run with them. One, following a shoestring TJN mapping exercise in Africa in 2005 and 2006, emerged from TJN to become Tax Inspectors Without Borders (TIWB) whose job is to help poorly-resourced tax authorities with under-trained staff in low-income countries deal with multinationals, which can field armies of highly paid lawyers and accountants — not to mention dollops of well-aimed political financing, and worse — to get the tax results they need. TIWB is helping redress the balance:

“Recently a team came back from meeting one company so excited,” relates another [Jamaican tax official]. For the first time ever when dealing with a large taxpayer, “our people did the talking and the other side sat dumb”, struggling to answer the questions.”

At a meeting in Nairobi in 2007 we set up Tax Justice For Africa, and also started implemented the idea to set up a Financial Secrecy Index (FSI) to identify the most important recipients of looted money. The idea, as outlined in 2007, was to create an antidote to widespread corruption rankings (such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index) which pointed identified poor (mostly African) countries as the ‘most corrupt’ — while ignoring those rich-world countries that were welcoming all the stolen and illicit loot and shrouding it in secrecy. The first FSI was launched in 2009. Two years later, the launch of Nicholas Shaxson’s book Treasure Islands helped push tax havens into the mainstream media (a film based loosely on the book was viewed a million times within a couple of weeks of release.)

An agenda that appeals across the political spectrum

One of the great strengths of TJN, beyond the fact that it is and has been proven absolutely right about the issues, is that has striven to appeal across the political spectrum, from left to right. The problem of tax havens is, after all, a story about the corruption of global markets – and who is to say that the fight against corruption is the exclusive preserve of left or right?

The story of the years that followed these beginnings become increasingly complex, as more and more organisations join the tax justice movement, as TJN grows in strength and number, and as it takes on a broader range of issues.

The Tax Justice blog has been instrumental in helping lay out the broad outlines of what we sometimes call the Tax Justice Consensus, which TJN has found to be a powerful and internally coherent framework for understanding the world, which ranges far beyond the somewhat technical world of international tax cooperation treaties.

A number of influential books and reports have emerged from TJN. The most comprehensive single account of tax havens and the tax justice consensus remains Nicholas Shaxson‘s acclaimed Treasure Islands; our daily blog is complemented by our flagship newsletter Tax Justice Focus; by Richard Murphy’s prolific and widely read Tax Research UK blog (which is separate from TJN); alongside a range of reports such as the Price of Offshore (March 2005, updated in July 2012) and ‘Tax Us If You Can’ (September 2005, updated in July 2012.)

Our fast and flexible operating model allows us to push continuously into new areas and add to this ever-expanding body of work: for instance the Finance Curse; an emerging focus on Tax Justice and Human Rights; and a new, more explicit focus on the ‘competitiveness’ of nations and the race to the bottom between them.

TJN separated out its research and advocacy activity from grassroots campaigning in 2013: now the Global Alliance for Tax Justice, which campaigns on tax justice issues, is organisationally separate from us; there are also numerous tax justice chapters around the world calling loudly for some serious action on tax havens.

But the fight remains a David versus Goliath one, as can be seen from our miniscule headquarters in Chesham, England, which looks like this.

We’re very happy to receive comments about this history. If anyone feels they or someone else has been unfairly or erroneously treated, or just want to add an interesting detail, please let us know. It will be stored permanently on our Offshore History page.