A New Year Wrapper!

The Authority of Financial (Mis)Conduct

As the first decade of the 21st century came to a close the hangover from two decades of excess in the financial sector finally set in. Banks collapsed and threatened to take down major economies with them. It has been a long hangover, and many are still suffering from it.

As the media, regulators and policy makers finally started to pay attention to the financial sector a series of scandals began to emerge. These ranged from carelessness to criminality on the part of major banks responsible for the administration of large parts of the economy.

Central to this issue was the standards of conduct and behaviour of many of the individuals working in banks. At lower levels the Libor fixing scandal showed a cavalier disregard for the law, with traders offering small gifts for rigging multi trillion dollar financial markets. At the top, leaders presided over institutional criminality, setting up entire divisions to deal in illegal or illicit funds.

The misconduct of the financial sector was widely accepted by government and policy makers as being a powerful factor behind the financial crisis. In an attempt to show that they were grappling with the problem, the UK Government even renamed their financial regulator – the Financial Standards Authority – the ‘Financial Conduct Authority’.

The UK Parliament’s Banking Commission, reporting in 2013, described the conduct of bankers as “appalling” and lamented the lack of any individual accountability for the many failings contributing to financial crisis. In particular it said:

“Remuneration has incentivised misconduct and excessive risk-taking, reinforcing a culture where poor standards were often considered normal. Many bank staff have been paid too much for doing the wrong things, with bonuses awarded and paid before the long-term consequences become apparent.”

It therefore came as some surprise that on New Year’s Eve it was revealed that the Financial Conduct Authority has dropped an investigation into the very thing it was set up to regulate, conduct.

One does wonder (or rather hope) that someone at the FCA started their New Year’s celebration early, got drunk, and made a rash and unauthorised announcement; that would appear to be the most rational explanation for the change in policy. Sadly it is not so, the news was apparently snuck out in an update to the organisation’s business plan. No official announcement from the FCA had been made at all, perhaps they hoped no one would notice.

Why has this been done? We can only speculate, but this latest move is just one part of a worrying in shift in the UK government’s attitude towards financial institutions. Currently the FCA is looking for a new director after the previous Director, Martin Wheatley, was fired (or rather, his contract was not renewed without his consent). As one senior conservative lawmaker put it, Mr Wheatley was seen as too tough on the banks.

The person tipped for the top post now should be much more agreeable. Tracey McDermott is the person who would have been ‘ultimately responsible’ for cancelling the review.

Given that conduct can be influenced by incentives, one does have to be concerned by the revolving door – how ferocious will we expect to see regulators if they believe that their future personal financial security relies on the people they are regulating?

This is not just about banker bashing, as Green MEP Molly Scott Cato put it eloquently in a letter to The Independent:

“In an economy where money is created in the private sector based on debt, a banking licence represents an extraordinary power granted to a small number of corporations by the state. Strict regulation of their activities, particularly when their risks are guaranteed by the public, is therefore essential.”

Nepal trys to jam shut the revolving door

Perhaps the British Government should be looking to Nepal for some inspiration. The Nepalese government has become increasingly concerned about the gigantic sucking sound coming from the nations nascent financial sector after a number of high profile government officials and regulators left to join major banks.

Fearful of the impact that this may have on meaningful regulation the government has passed a new law which forbids the Governor, Deputy Govenor or Executive Director of the country’s central bank from joining a private sector financial institution.

Nepal does not keep statistics on what central bank employees do after they leave office, but a snap poll conducted by the Nepalese newspaper Republica found two dozen financial institutions that had recruited from the regulator.

Banks in no tax shocker

And if all the above wasn’t enough, it turns out that many banks pay no corporation tax either. Thanks to a change in European law, banks in the European Union now have to report on a country by country basis, which reveals how much profit is being made in each country and how much tax has been paid on those profits.

Reuters has been though some of the filings for the UK and found that a number of large banks pay virtually no tax in the UK. A study looked at just the corporate and investment banks operating in Britain, as retail banks (for example HSBC and Barclays) have a very different business which makes them difficult to compare. It found that in total 7 banks paid just $31m in corporation tax on profits of $5.3bn. Five of the banks, JP Morgan, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Deutsche Bank AG, Nomura Holding and Morgan Stanley paid no corporation tax at all. JP Morgan Limited in the UK still somehow found the cash to pay a $400m dividend according to their annual accounts.

Reuters then followed up finding two more banks, Credit Suisse and Citigroup, with no corporation tax bill in the UK. The final study looked at 10 banks and found $40 billion in fees, $6.5 billion in profit but just $205 million in corporate income tax.

All of the banks in the Reuters study are headquartered abroad. Why is this important? Because banks operating in the UK also have to pay a ‘bank levy’. This is a charge on the value of a bank’s balance sheet, regardless of whether it is making a profit or not. It was designed as a payback from the banking sector to all of the help it received from the crisis during the crash.

Foreign owned banks are treated differently from British banks under the current rules, British head-quartered banks see the charge on the entire balance sheet of the global company, foreign banks only pay on their British balance sheet. This difference is one reason why global banks headquartered in the UK such as HSBC and Standard and Chartered have threatened to move offshore.

In response the UK government has agreed to halve the bank levy, and in the future will only apply it to the UK balance sheet of UK banks. How will they make up for the loss of income? Increase the rate of corporation tax – yes, you couldn’t make it up.

Other British banks have complained that the banking levy falls disproportionately on smaller institutions. They have a point; a building society like the Nationwide which only operates in the UK has to pay the levy on its entire balance sheet and doesn’t have the option to shift masses of profits offshore to their foreign operations. But isn’t the answer just to address multinational profit shifting across the board?

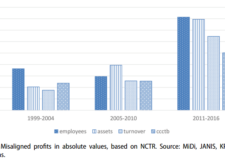

The picture given by Reuters looks at the UK in particular, but a study by Professor Richard Murphy of City University last year showed the same trend happening across Europe. Murphy looked at 27 European banks and revealed more profits being declared by relatively fewer employees in bank entities based in tax havens against lower profits and more employees in bigger economies. Clear evidence of profit shifting. Murphy’s study can be found here.

More work is forthcoming on this mine of information the banking sector has been compelled to release by the European Union in the coming months from the TJN.

An embarrassment of Riches

Why is it the Wrapper is full of the same stories every week? Big banks and wealthy individuals get away with murder, government does nothing.

The New York Times provides an answer. In an extensive article they describe not only how the wealthy use complex tax loopholes to dodge billions in taxes, but also the millions they invest in politicians, lobbyists and campaigners to keep those tax loopholes open.

It describes an “income defense industry” that has created a “private tax system” for the wealthy and is providing much of the funding for the early US presidential campaigns.

What will the rest of us do when all the money has been sucked away? Well there is always the age old tradition of watching others spend it. A documentary from the BBC recently looked at the industry which enables millionaires to waste their cash in style.

There are the traditional methods such as expensive suits, watches, art, etc, and then there are the innovators (childrens’ parties in a 30 bedroom country retreat, bespoke flower arrangements, personally delivered invitations from an elf).

Those with a strong stomach can watch the programme here, but be warned: this really does illustrate why leading artist Peter Kennard described the art world as ‘disgusting’.

Tax haven goes bankrupt

What a difference a year makes. In March 2015 Forbes reported on how Puerto Rico had become a tax haven within the United States, offering zero percent taxation on some dividends, income and capital gains. As Mohnish Pabrai, quoted by Forbes put it:

“The way the U.S. tax code is written, I could be on Mars and be taxed on intergalactic income but not if I’m sitting on this island in the Caribbean. It’s kind of in a twilight zone,”.

Puerto Rico hoped to exploit a loophole in the US tax system which allowed them to be part of the US, but to run a separate tax regime from the rest of the country in order to attract people to the island and boost economic activity.

Has it worked? We will let you decide for yourself, the government of Puerto Rico defaulted on its debts on Jan 1st.

P.S. For information about another tax haven heading for the financial rocks, read this Guardian long read article about the British Channel Island of Jersey, which for decades has based its development strategy on tax competition.

Happy New Year!

Leave a Reply